Prefer to Watch Instead?

Prefer to watch instead of read? This video covers the same framework explained in this article. Watch the full presentation, or continue reading below for the written guide. (Video length: 1 hour and 17 minutes)

Introduction

One of the most difficult questions pet owners face is: “How do I know when it’s time?”

Too often, the answer is frustratingly vague: “You’ll just know” or “They’ll give you a sign.” These well-meaning responses aren’t actually helpful—and they can leave families searching for a perfect moment that doesn’t exist.

The reality is different, and we believe more helpful: it’s not a moment, it’s a window.

What Is The Euthanasia Window?

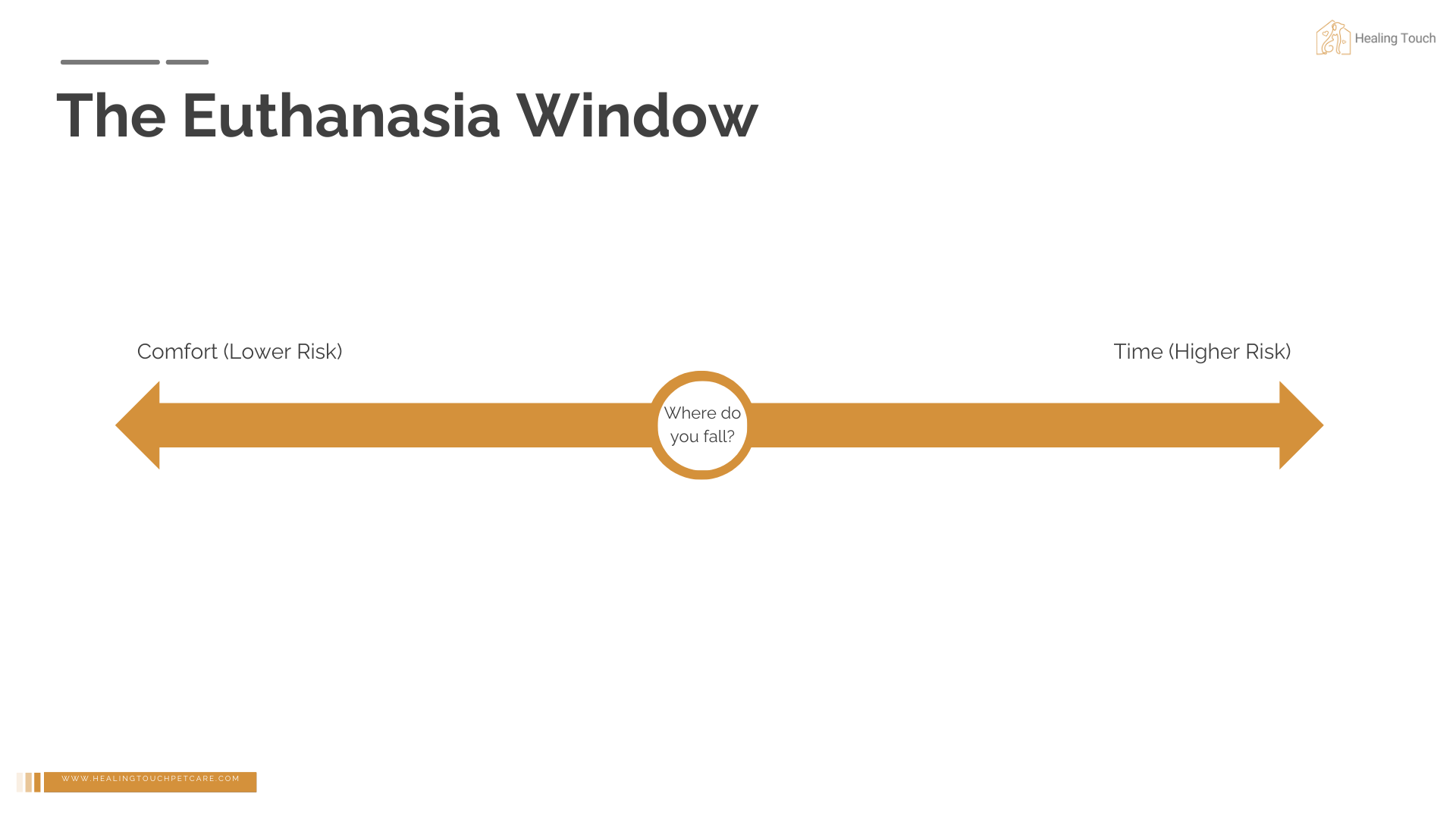

The euthanasia window is a period of time—not a single moment—where the decision to euthanize is medically and ethically appropriate.

Think of it as a spectrum. On one end, you have maximum comfort for your pet. On the other end, you have maximum time together. As your pet progresses through their illness or advanced age, you move along this spectrum from comfort toward time.

At the very end of the time spectrum is natural death. Earlier in the window, when comfort is higher, is where many families choose euthanasia.

There is no single “right” place to be on this spectrum. Rather, there’s a range of circumstances that make euthanasia medically appropriate, and within that space, a combination of factors that make the decision as peaceful as it can be for everyone involved.

How Do You Know If You're in the Window?

If you have any doubt about whether you’re in the euthanasia window, the most important thing you can do is consult with your veterinarian. They can tell you if your pet is medically within the window where the decision is humane and ethically appropriate—this isn’t a determination you need to make alone. We can also help provide clarity through our Quality of Life Consultation.

That said, there are some indicators that suggest you may be in the window. Your pet has been diagnosed with a terminal condition. Or your pet has been diagnosed with a condition that you are unable, or unwilling, to treat—and both of those situations are valid. If your veterinarian has started using words like “palliative care,” “hospice,” or “keeping them comfortable,” that’s often a signal you’ve entered this space. And perhaps most tellingly, if quality of life has become more than just a passing thought—if you find yourself regularly assessing whether your pet is still enjoying life—you’re likely somewhere in the window.

Here’s what’s crucial to understand: just because you’re within the window doesn’t mean you need to act immediately. The window isn’t a narrow deadline—it’s a span of time during which the decision is appropriate. It’s about creating space for the decision, not rushing it. Some families are in the window for days, others for weeks or even months. There’s no single “right” moment within that span. What matters is that you’re paying attention, staying connected with your veterinarian, and making the decision when it feels right for you and your pet.

Something to Keep In Mind

Before we go further, we want to take a moment to address a common feeling with regards to this decision. It’s common to feel as though by electing euthanasia, you are choosing for your pet to die. It’s important to us that you know that by making this decision You are not choosing whether your pet will die.

Their disease, their age, their prognosis—these things have already made that decision. What you’re choosing is not “if” they will die, but how.

It’s a small reframe, but it’s powerful. Instead of “I’m choosing for my pet to die,” it becomes “If this has to happen, this is how I want it to happen.” That shift can bring more peace to the process and help you maintain some control over how things unfold.

Understanding Both Sides of the Spectrum

The Comfort Side (Earlier Intervention)

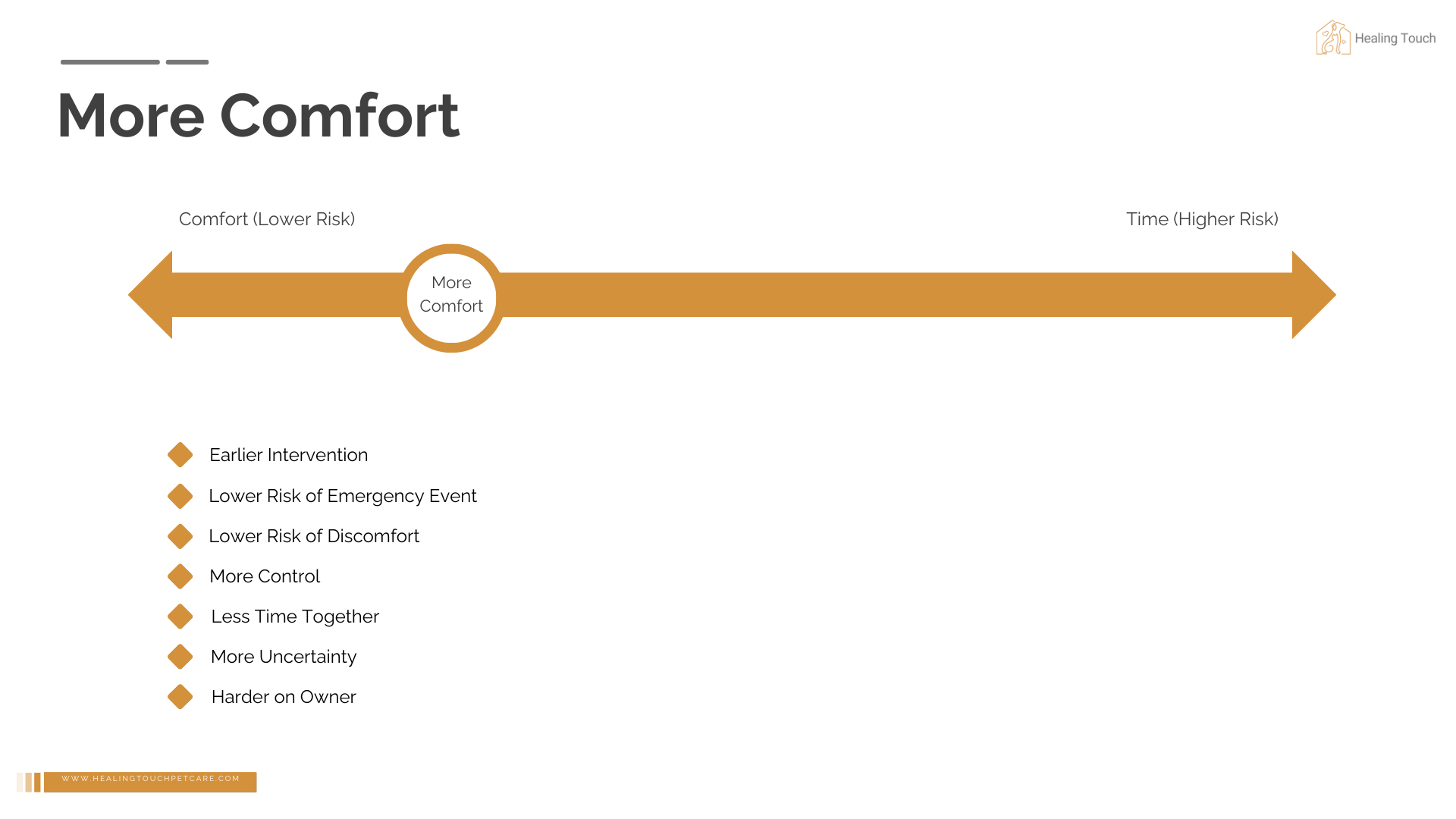

Choosing to act earlier in the window means prioritizing your pet’s comfort over additional time together. This approach comes with significant benefits: you’ll face a lower risk of emergency situations and a lower risk of prolonged discomfort for your pet. Perhaps most importantly, you maintain more control over the process—who will be there, where it will happen, and the timing of your goodbye.

But this choice isn’t without its challenges. There will be less time together, and with that comes uncertainty. “Is it too soon?” becomes a persistent question. The emotional weight of that uncertainty can be heavy, precisely because you’re making the decision while your pet still has some good days left.

The Time Side (Later Intervention)

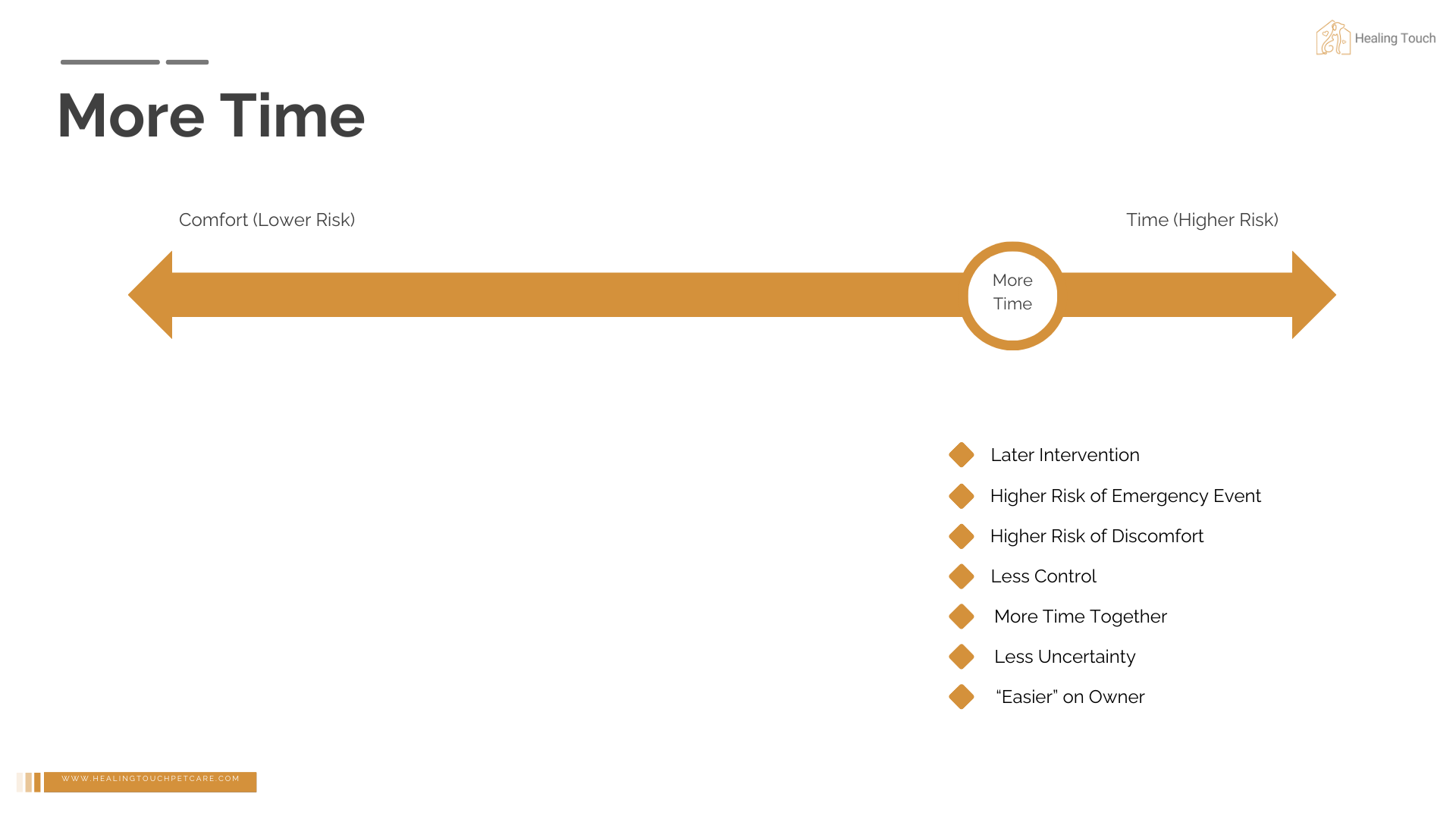

Waiting longer in the window means you get more time with your pet. That additional time is precious, and there’s less uncertainty about the decision because medical decline becomes more apparent. In some ways, this path is emotionally easier—when your pet’s condition has deteriorated significantly, the need for euthanasia becomes clearer. You’re not wrestling with “is it time?” in quite the same way.

However, this approach carries its own risks. The longer you wait, the higher the chance of an emergency situation arising. Your pet faces a higher risk of experiencing discomfort or crisis, and you may find yourself with less control over the circumstances. The decision you hoped to make at home, surrounded by family, might instead happen in an emergency room under duress.

Most families fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. Neither end is “right” or “wrong”—both carry different risks and benefits that you’ll need to weigh against your own values and circumstances.

"Denial" and Anticipatory Grief

We need to talk about something uncomfortable: denial.

Denial is part of the grieving process, and it often begins before death occurs. This is called anticipatory grief, and it’s completely normal, but often under recognized stage of this process.

Here’s the thing: denial is protective. It shields us from the emotional pain we know is coming. But in our experience working with families, denial often means owners aren’t acting soon enough to meet their own goals for their pet’s end of life.

This isn’t about rushing anyone. It’s about creating space for the decision before you’re in crisis mode.

Why does this matter? Because in our experience, we’ve never had a family tell us “I wish we’d waited longer.” But nearly every week, we hear families say “I wish we’d made the decision sooner.”

By understanding that denial might be influencing your thinking, you can push through it just enough to plan—not necessarily to act, but to prepare.

Factors That Influence Where You Fall in the Window

Deciding where you want to be on the comfort-versus-time spectrum isn’t simple. Many factors influence this decision, and they’re all valid.

Your Goals

Before anything else, you need to identify what you’re trying to achieve. Are you hoping to maximize your pet’s comfort, even if it means potentially less time together? Or are you hoping to maximize time, accepting a higher risk of decline or emergency? Perhaps you’re somewhere in between these two priorities.

Some families are adamant about avoiding an emergency situation, prioritizing the ability to maintain control over the process—who will be present, where it will happen, whether there’s time for special rituals like reading a poem or saying a prayer. Others want their pet to pass at home rather than at a clinic, or are considering allowing a natural death.

If you’re considering a natural death, it’s important to understand that this choice requires significant preparation and ongoing management. You’re not just deciding to let nature take its course—you’re committing to intensive monitoring of comfort and symptoms, potentially over an extended period. Even with excellent care, you may still find yourself in an emergency situation if something goes wrong during the dying process. This doesn’t mean natural death is wrong, but it’s important to understand what you’re taking on.

Only you and your family know what will be easier for you to come to peace with afterward. Will it be the uncertainty about time left, or the certainty that your pet didn’t suffer unnecessarily? Either way, it’s never going to be easy—you’re simply choosing your hard.

Medical Factors

The disease itself plays a significant role in how wide your window is and how much time you have from maximum comfort to natural death. Some diseases, like chronic kidney disease, progress slowly and can be detected early, giving you a wider window to work with. Other diseases, like osteosarcoma (bone cancer), are harder to detect and may progress rapidly—by the time you catch them, you may already be late in the window with limited time to make decisions.

Predictability matters too. A condition with steady, predictable decline is very different from one with unpredictable symptoms. When you don’t know when a seizure might strike or when respiratory distress might suddenly worsen, managing day-to-day life becomes more challenging. This unpredictability often pushes families toward the comfort side of the spectrum simply because they can’t reliably keep their pet comfortable.

The treatment options available to you also factor heavily into this decision. Are there effective treatments your pet will tolerate? Are these treatments curative, or are they simply supportive measures that might buy some time? Sometimes the side effects of treatment are significant enough that pursuing them doesn’t feel worth the additional burden on your pet. When treatment options are limited or come with substantial downsides, many families shift their focus to comfort care and monitoring quality of life closely.

Finally, access to supportive care—pain management, appetite stimulants, mobility aids—can significantly extend the time side of the window while still maintaining comfort. If you can effectively manage pain and other symptoms, you may be able to give your pet more good days without compromising their wellbeing.

Access to Care

Your proximity to veterinary services matters more than you might think. A family living ten minutes from a 24-hour emergency clinic operates with a different set of considerations than a family living an hour away. When the nearest emergency room is in Appleton or Green Bay and you’re in Sheboygan or Plymouth, that hour-plus drive with a pet in distress weighs heavily on decision-making. If avoiding an emergency situation is one of your goals and you live further from emergency care, you may need to make the decision somewhat earlier to ensure you don’t end up in that scenario.

Access to in-home services also shapes your options. In-home euthanasia allows you to avoid the stress of transporting your pet and gives you more control over the environment. Similarly, if in-home hospice care is available in your area (though it’s not terribly common in veterinary medicine), it can extend quality time without the repeated stress of vet visits.

Your relationship with your veterinary team matters as well. Do they offer quality-of-life consultations? Can they provide guidance and support as you navigate this process? Having a veterinarian who will work with you to monitor symptoms and adjust comfort care can make a significant difference in your ability to keep your pet comfortable at home.

Your Pet's Individual Traits

Every pet is different, and these differences affect how you navigate this process. Some pets are masters at masking pain and illness—cats especially can hide decline for years. If your cat has been concealing health issues for the past 15 years of its life, don’t expect sudden transparency about suffering now. This means you’ll need to rely heavily on subtle changes in behavior and historical comparisons: how did they act in their prime, and how does that compare to now?

The ease of providing care matters too. Some pets simply cannot be medicated without extreme stress for everyone involved. If your pet’s condition requires frequent vet visits for monitoring—blood work, examinations—and every trip to the clinic is a traumatic ordeal for both you and your pet, that reality will influence where you fall in the window. Managing the disease to maintain comfort becomes exponentially harder when basic medical care is a battle.

Size plays a practical role as well, particularly for large dogs with mobility issues. The physical strength required to help a large pet get around, or to lift them into a car for transport, is a real limitation for many owners. Your pet’s age factors in too—younger pets may tolerate aggressive treatment better than elderly ones, and as pets age, many conditions shift from curable to manageable, requiring more palliative care approaches.

Your Personal Circumstances

This is where guilt often creeps in, but these factors matter whether we acknowledge them or not. It’s better to be honest about them so you can give yourself grace in the process.

Your physical capacity directly affects what care you can provide. If you’re dealing with your own mobility limitations, chronic health conditions, injuries, or the effects of aging, the type and intensity of care you can offer your pet is naturally limited. This isn’t a shortcoming—it’s simply reality. The availability of a support system—family, friends, neighbors who can help—can offset some of these limitations, but not everyone has that support readily available.

What else is happening in your life matters too, even though it can feel selfish to acknowledge. If you’re caregiving for children or aging parents, if you have demanding work responsibilities, if there are major life events like weddings or funerals on the horizon—these all compete for your emotional bandwidth and physical time. How much space do you have on your plate right now to provide intensive end-of-life care? It’s okay if the answer is “not much.”

Financial resources are perhaps the most guilt-inducing factor to acknowledge, but they’re real. It’s okay to say that because of cost, you’re choosing not to pursue aggressive treatment. It’s also okay to simply not have the financial means to pursue expensive treatments. Your pet cares about your love, not how much money you spend. You do the best you can with what you have, and that’s enough.

Your living situation presents practical considerations as well. If you have a pet with mobility issues and you live in a third-story apartment, winter weather and icy stairs create genuine safety concerns. The risk of your pet slipping, falling, and ending up in an emergency room might be enough reason to make the decision somewhat sooner. That’s not selfish—it’s acknowledging the practical reality you’re working with.

Emotional Factors

Where you are in the window profoundly affects how you feel about the decision. Early in the window, you’ll likely wrestle with questions like “Is it too soon?” and “Am I giving up on them?” There’s often a fear that you’re betraying your pet or giving up copious amounts of time you could have had together. These feelings are completely normal.

Here’s something that might bring comfort: in our experience, owners are typically not making decisions so early that they’re giving up months or years of natural time. More often, it’s weeks—sometimes days. And in our work with over a thousand families, we’ve never once had someone call back to say they wished they’d waited longer. Nearly every week, however, we hear families say they wish they’d made the decision sooner. This doesn’t make your decision easier, but it provides context for what you’re wrestling with.

Later in the window, the questions shift. “Am I being selfish for keeping them here?” and “Have I waited too long?” become more prominent. Some families even feel guilty about feeling relief that the end is approaching. If you’re worried you’re being selfish for wanting more time, let us be clear: it’s not selfish to want more time with your pet. That’s not selfishness—that’s human nature. You just need to be aware of the risks that come with waiting and manage your pet’s comfort diligently.

Previous experiences shape your emotional response too. First-time pet owners typically wait longer, sometimes ending up in emergency situations simply because they don’t know what to expect. Previous emergency euthanasias often make people want to act sooner to avoid repeating that trauma. Conversely, a previous difficult euthanasia experience might make you more hesitant, especially if there are unresolved feelings making the current decision harder.

Family Dynamics

It’s not uncommon for different family members to disagree about whether it’s time or where you should fall in the window. Often, these disagreements arise not because anyone is wrong, but because different people see different things.

Consider a pet with dementia. If one family member works mornings and spends afternoons and evenings with the pet, they’re witnessing the sundowning—the worsening of dementia symptoms as daylight fades. Meanwhile, a spouse who works overnight and only sees the pet in the mornings experiences a different reality, seeing symptoms that are present but less severe. Neither perspective is wrong; they’re simply viewing the situation through different lenses based on the time they spend with the pet.

Quality-of-life assessments completed independently by each caregiver can help bridge these gaps. When you compare results, you might discover patterns: “I noticed your mobility score was really low—what are you seeing that I’m not?” This opens dialogue about who’s home during which hours and what symptoms appear at different times of day.

Social pressure from others can complicate things too. Society is quick to judge, not just about the decision to euthanize but also about how you grieve afterward. You might have that cousin at Thanksgiving who takes one look at your pet and says, “Wow, they’re looking rough,” when you hadn’t fully registered the decline yourself. Because you see your pet every day, you notice the gradual change from yesterday to today. Your cousin sees the change from six months ago to now—a much more dramatic difference. There’s validity in that outside perspective, but you can’t let external pressure create additional distress. At the end of the day, you’re the one who has to make and live with this decision.

Timing and Seasonality

The calendar matters in ways both medical and practical. Some conditions worsen seasonally—mobility issues become more challenging in winter cold, while cardiac or respiratory issues can deteriorate in summer heat. These seasonal fluctuations might influence when you need to act.

Life schedules factor in as well. School years versus summer breaks, vacations, weddings, work commitments—you’re consciously or subconsciously considering all of these as you think about timing. It’s natural to struggle with decisions around holidays or special occasions. Many families want to get their pet through the holidays or have their children home from college to say goodbye.

It’s okay to have these preferences, but you need to balance them with flexibility. If you’re hoping to wait until the holidays, you have to accept that you might not make it that far, or you might end up in an emergency situation. There are ways to include people who can’t be physically present—video calls aren’t the same as being there, but they allow some form of connection.

Aftercare plans can influence timing too. If you’re in Wisconsin in January and you want to bury your pet on your property, the frozen ground creates a practical constraint. It’s perfectly acceptable to factor this into your decision-making. Remember, the window is that period where euthanasia is ethically and medically appropriate—it’s okay to make the decision based on practical considerations like weather or ground conditions, as long as you’re within that window.

How to Navigate Within The Window

Quality of Life Assessments

This is the single most important tool you have for navigating the window. Quality-of-life assessments take something nebulous—”how is my pet doing?”—and add objectivity and data to it. They’re questionnaires that help you gauge your pet’s overall wellbeing across multiple dimensions.

One common misconception needs addressing: eating and drinking alone are not sufficient measures of quality of life. Many pets continue eating and drinking until they’re actively dying. These are life-sustaining biological functions, and your pet may maintain them even while experiencing significant decline in other areas. You need to look at the whole animal—mobility, pain levels, engagement with family, ability to do things they enjoy, hygiene, and more.

The best way to use these assessments is to establish a baseline. Do one assessment now, even if your pet seems fine. This gives you a reference point for comparison. Then track regularly—how often depends on your pet’s stage. For a younger pet or one with early-stage disease, maybe monthly is sufficient. As conditions progress, you might assess weekly. Toward the end, daily tracking can help you see patterns you might otherwise miss.

Be honest when you fill these out. It’s tempting to soften the truth, but accurate assessments help you make better decisions. If multiple caregivers are involved, have everyone complete assessments independently, then compare results. This approach is particularly effective for addressing family disagreements because it reveals what each person is observing that others might not see.

Here is a link to a free PDF version of a Quality of Life Assessment

Prefer an electronic version?

We created Hospet, a completely free app for IOS and Android, to help track your pet’s quality of life over time. Learn more and download at this link.

End of Life Care Plan

Think of this as an advance directive for your pet. Write down your goals for their final chapter—what you want this experience to look like. Where do you want euthanasia to happen if you choose that path? At home or at the clinic? Who should be present? Are there any readings, prayers, or music you’d like included? What are your aftercare preferences—cremation or burial?

Most importantly, create a backup plan for emergencies. It’s wonderful to hope your pet will have many more good days, that they’ll make it through the holidays, that decline will be gradual and manageable. But hope is not a plan. Having these decisions made when you can think clearly means you won’t be making them under duress if a crisis strikes.

This kind of advance planning doesn’t mean you’re giving up or wishing the end would come sooner. It means you’re being prepared and loving enough to spare yourself the agony of making impossible decisions in the worst possible moment.

Communicate with Your Veterinarian

When you receive a terminal diagnosis, there’s often so much shock that thinking clearly becomes nearly impossible. If you can’t ask questions in the moment—and no one would fault you for that—follow up afterward. Schedule a follow-up appointment, send an email, or call to get the answers you need.

There are several essential questions you should eventually ask. First, what does disease progression look like if you do nothing? Understanding the natural trajectory of the disease helps you know what to expect if you choose not to pursue treatment and instead focus on monitoring and comfort care.

Second, what treatment options exist, and what do they entail? You need to understand not just what’s available, but what each option costs, what the side effects are, what the chances of success look like, and whether the treatment is curative or merely palliative. Sometimes the answer to this question will immediately clarify your decision—if the only treatment available is palliative with severe side effects and modest chances of adding a few weeks, you might decide it’s not the right path.

Third, what’s the timeframe you’re working with? No one can give you an exact date, but understanding whether you’re looking at weeks versus months versus years helps you plan. This timeframe, combined with your understanding of disease progression, gives you a sense of how wide your window might be.

Finally, ask about quality-of-life consultations. Regular check-ins with your vet about comfort and progression can provide invaluable guidance as you navigate this process.

If you’re in a crisis situation and your vet recommends immediate euthanasia, it’s okay to ask one more question: “Is there anything we can do to keep them comfortable for just a day or two so I can process this?” Often, there is. Even one extra day can make a significant difference in your ability to come to terms with what’s happening. If the answer is no, at least you asked—you won’t be left wondering weeks later whether you could have had more time to prepare or to let family say goodbye.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect moment. There’s only a window of time where euthanasia is medically and ethically appropriate.

This decision is complicated. It involves medical factors, personal circumstances, emotional readiness, family dynamics, timing, and more. Whether you choose to act earlier or later in that window, neither decision is right or wrong. Both carry different risks and benefits.

What matters is understanding the influences you’re dealing with so you can make an intentional, values-aligned decision that honors both your pet and your family.